Ice Treasures of Uzbekistan: Where Sky Meets Earth

High in the mountains, where the air grows thin and the sky seems infinitely close, begins a special world — the nival-glacial belt. This realm of snow and ice, situated above 3,500 meters above sea level in Uzbekistan's mountains. Here, among the snow-capped peaks of the Western Tien Shan and Gissar-Alay, nature has created a unique water conservation system upon which the lives of millions of people depend in the valleys below.

Picture this: while cotton fields bloom and melons ripen in Uzbekistan's valleys, high in the mountains, natural reservoirs quietly work — glaciers and snow cover slowly accumulating and carefully releasing precious water exactly when it's needed most.

Small but Important Guardians

Unlike the world famous glaciers, Uzbekistan's glaciers are more modest in size but no less important. According to 2014 data, the republic had 411 glaciers with a total area of nearly 100 km². Most are concentrated in the basins of three major rivers — Pskem, Kashkadarya, and Surkhandarya.

The country's largest glacier, Pakhtakor, covers only 2.8 km² — roughly the size of a small city district. But don't underestimate these modest ice masses. During dry summer months, when rain becomes scarce, glaciers provide 10–25% of river flow, and in particularly dry years their contribution becomes even more significant.

Modern research reveals an interesting picture: in the Pskem River basin, 213 glaciers covering 59 km² were identified by 2023, while neighboring basins of the Koksu, Akbulak, and Akhangaran rivers contain another 30 small glaciers with a total area of just 1.6 km².

Snow — The Main Hero of the Water Story

If glaciers play the role of strategic reserve, then snow cover is the primary water supplier for Uzbekistan. Snow falling during the cold period from October to March forms 70–85% of annual river flow. This is a true treasure that nature accumulates in winter and generously releases in spring and summer.

Spring-summer floods begin in mid-March and can last up to 180 days on rivers with glacial-snow feeding. This is when rivers transform into full-flowing streams carrying life to arid regions. The period from April to September accounts for 77–80% of annual flow, which perfectly suits the needs of irrigated agriculture.

Scientists distinguish four types of rivers in the Amu Darya and Syr Darya basins: glacial-snow, snow-glacial, snow, and snow-rain fed. As you can see, snow is present in all types — this emphasizes its key role in the region's water regime.

Hidden Ice Riches

Besides regular glaciers, a special world of underground ice exists in Uzbekistan's mountains. There's no permafrost here like in northern countries, but there are four unique types of ice formations:

Buried glaciers — like sleeping giants covered by thick blankets of rock. They slowly melt under their stone protection, gradually transforming into "dead ice."

Dead ice — remnants of former glaciers that stopped moving but continue to exist as icy monuments to the past.

Ice in glacial deposits — ice inclusions among stones and sand left by ancient glaciers.

Rock glaciers — amazing flows of rock material bonded by ice that slowly creep down slopes like stone rivers.

In the Pskem River basin alone, 257 such formations were counted by 2023 — an entire hidden world of underground ice.

Climate Is Changing, But Gently

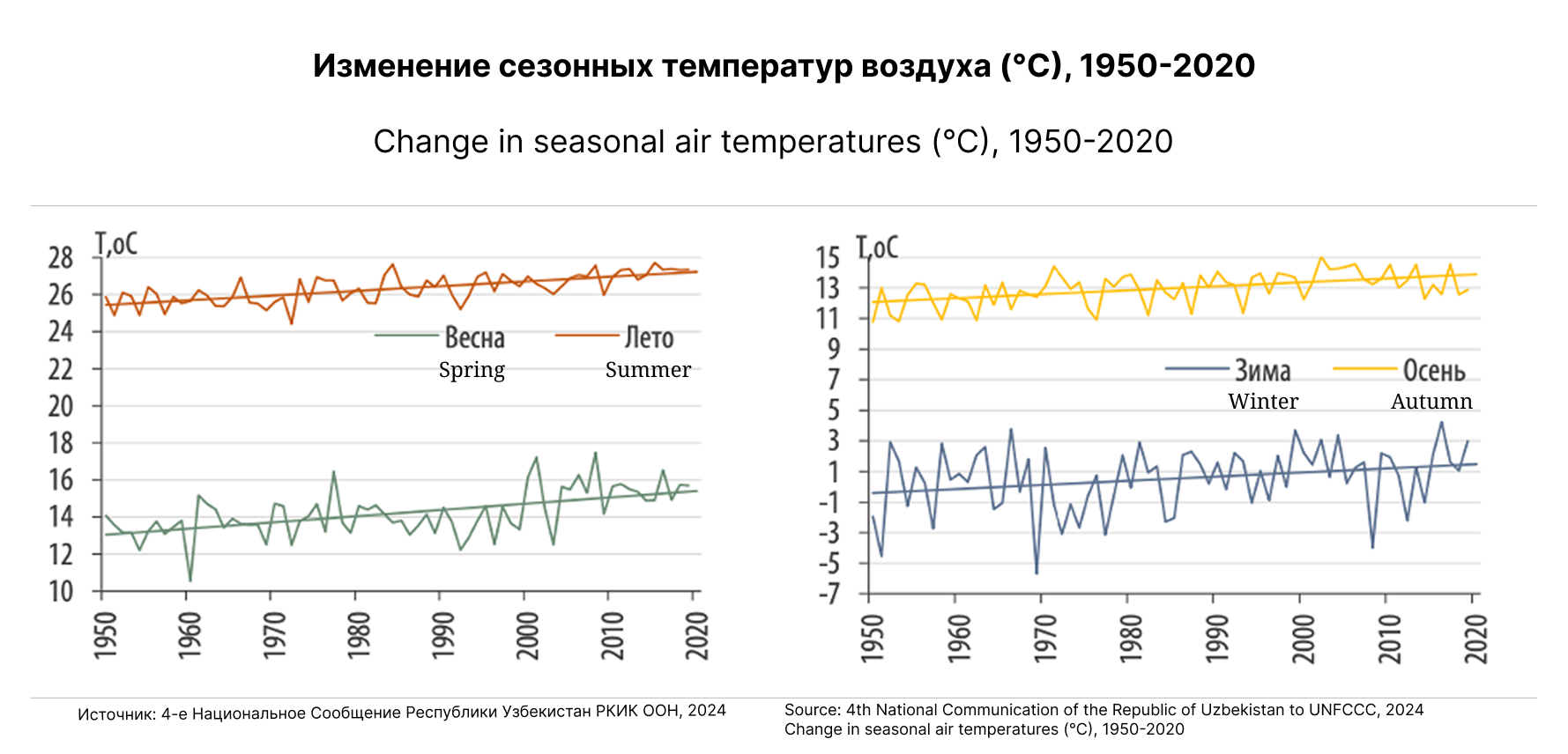

Over the past 130 years, Uzbekistan's climate has indeed changed. From 1950 to 2020, temperatures rose gradually:

- Spring temperatures increased from 13°C to 15°C

- Summer temperatures — from 25°C to 27.5°C

- Autumn temperatures — from 12°C to 14°C

- Winter temperatures also showed a warming trend

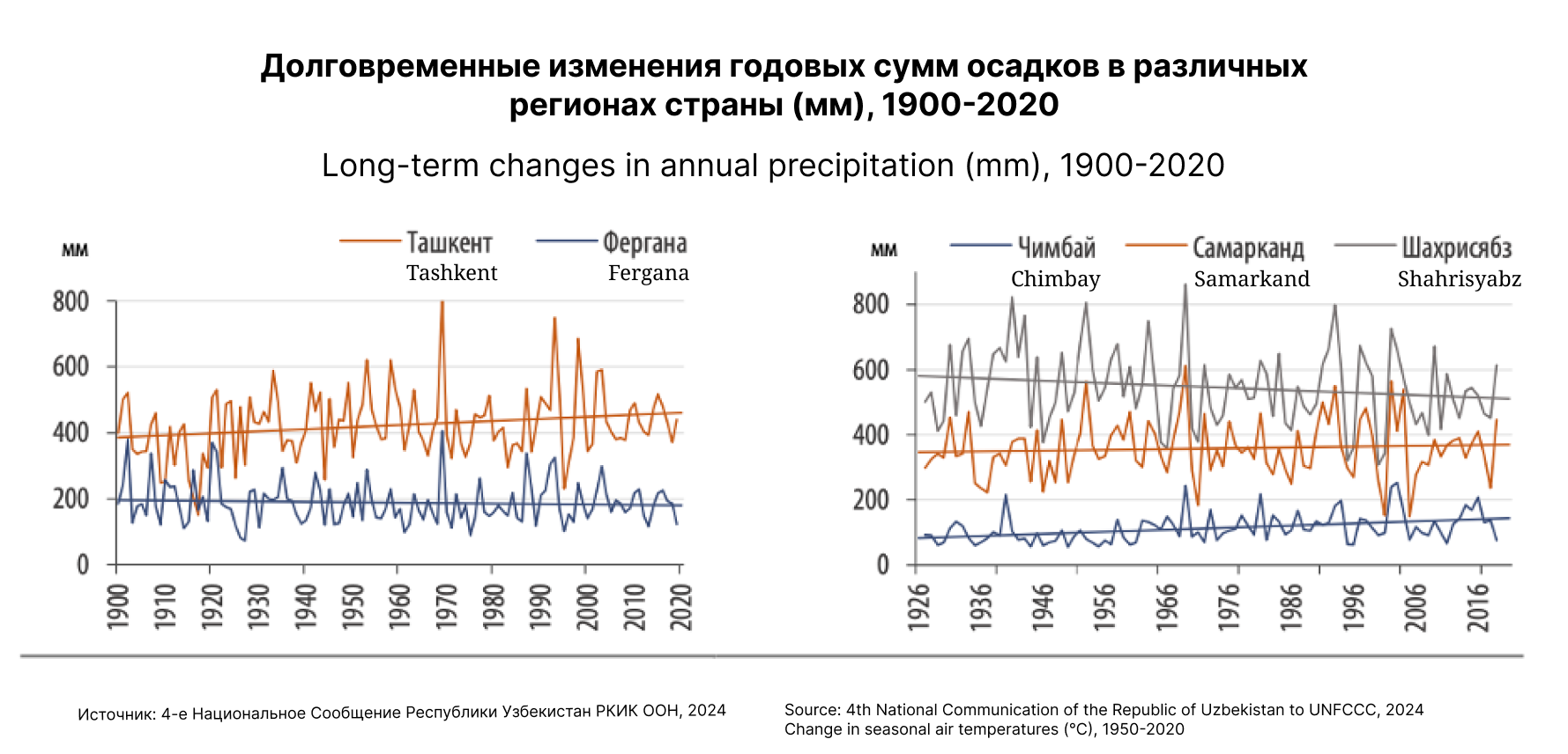

At the same time, precipitation remains relatively stable, though distribution is uneven: Tashkent and Samarkand receive 350–450 mm annually, while Fergana and Chimbay get only 100–200 mm.

Water — The Foundation of Life

Uzbekistan is a country where water is literally worth its weight in gold. 86% of all water resources goes to irrigated agriculture, which feeds the 35 million population. Underground and drainage waters provide an additional 9.43 cubic kilometers per year, but the main role is played by surface waters fed by mountain snow and glaciers.

Looking to Tomorrow

Scientists predict that by 2100, temperatures in Uzbekistan could rise by 5–6°C. This means earlier snow melting and changes in river regimes. Summer flow in some basins is expected to decrease by 10–37%.

However, this is not cause for panic but a call to action. Uzbekistan's nature has adapted to arid climate for centuries, and people have learned to wisely use every drop of water. Modern water conservation technologies, efficient irrigation systems, and careful treatment of glacial resources will help the country successfully cope with climate challenges.

Mountain Wisdom

The story of Uzbekistan's water resources is about how high-altitude glaciers and snow cover, occupying a tiny fraction of the country's territory, sustain an entire civilization. This is a reminder of how important it is to protect mountain ecosystems and understand their role in the region's water balance.

Glaciers act like wise elders — they don't rush to release their reserves but are always ready to help during the most arid periods. Snow cover works as a reliable partner, annually renewing its reserves and generously sharing them with the valleys.

Understanding these processes helps plan water use, develop efficient irrigation technologies, and prepare for climate change. After all, water is not just a resource — it's the foundation of life, and Uzbekistan's mountains continue to reliably store this treasure for future generations.

Go Back

Go Back