Invisible Guardians of Water

High in the snow-capped peaks of the Tien Shan and Dzungarian Alatau mountains, over 2,000 glaciers can be found across Kazakhstan. Spanning more than 1,000 square kilometers, these giant reserves of ice function as natural water towers, sustaining river flows during the dry summer months and providing vital water to agriculture and local communities.

While crops grow and rivers flow through the valleys in summer, glaciers in these mountain heights gradually melt, steadily releasing water. For centuries, this natural system has supported life, but in the last few decades, it has undergone significant changes.

A History of Disappearance

In the past 65 years, the area of Kazakhstan's glaciers has shrunk by 43%, with their total volume reduced by as much as 65%. The long-term trend is even more dramatic: in the Ile Alatau range, glaciers have lost 65–75% of their size since the mid-19th century. In other words, nearly three-quarters of the ice that once blanketed these mountains has vanished in just 150 years.

The Tuyuksu Glacier is one of the few glaciers that scientists have been monitoring continuously since 1957. Every year, this glacier becomes on average 40 centimeters thinner. To put it simply, if all the ice that melts each year turned into water, it would form a layer nearly half a meter thick spread across the entire surface of the glacier.

The statistics for individual ranges are striking as well:

- Ile and Kungey Alatau have lost 35% of their glaciers

- The Zhetisu Alatau has lost 43% of its ice cover

- In the northern Zhetisu Alatau, 44% of glaciers have disappeared

Dangerous Consequences

The retreat of glaciers brings new hazards. Since 2000, 43 new glacial lakes have formed in the Zhetisu Alatau. These lakes, held back only by unstable rock and debris, pose a serious threat to the valley communities below.

The Kishi Almaty river basin is particularly vulnerable:

- The total area of glacial lakes grows by 0.05 km² every year

- Steep slopes, with inclines up to 35°, create unstable conditions

- Earthquakes above magnitude 5.0 occur every 8–10 years

Together, these factors increase the risk of sudden lake outbursts and flash floods, threatening lives, key infrastructure, and the economy of the region.

Changing Snow Resources

Mountain snow in Kazakhstan is more than a pretty landscape - it's a seasonal water reserve. In major river basins, snowmelt accounts for over 50% of annual flow; in Kazakhstan's major southern watersheds, the combined contribution of snow and glaciers reaches as much as 72%.

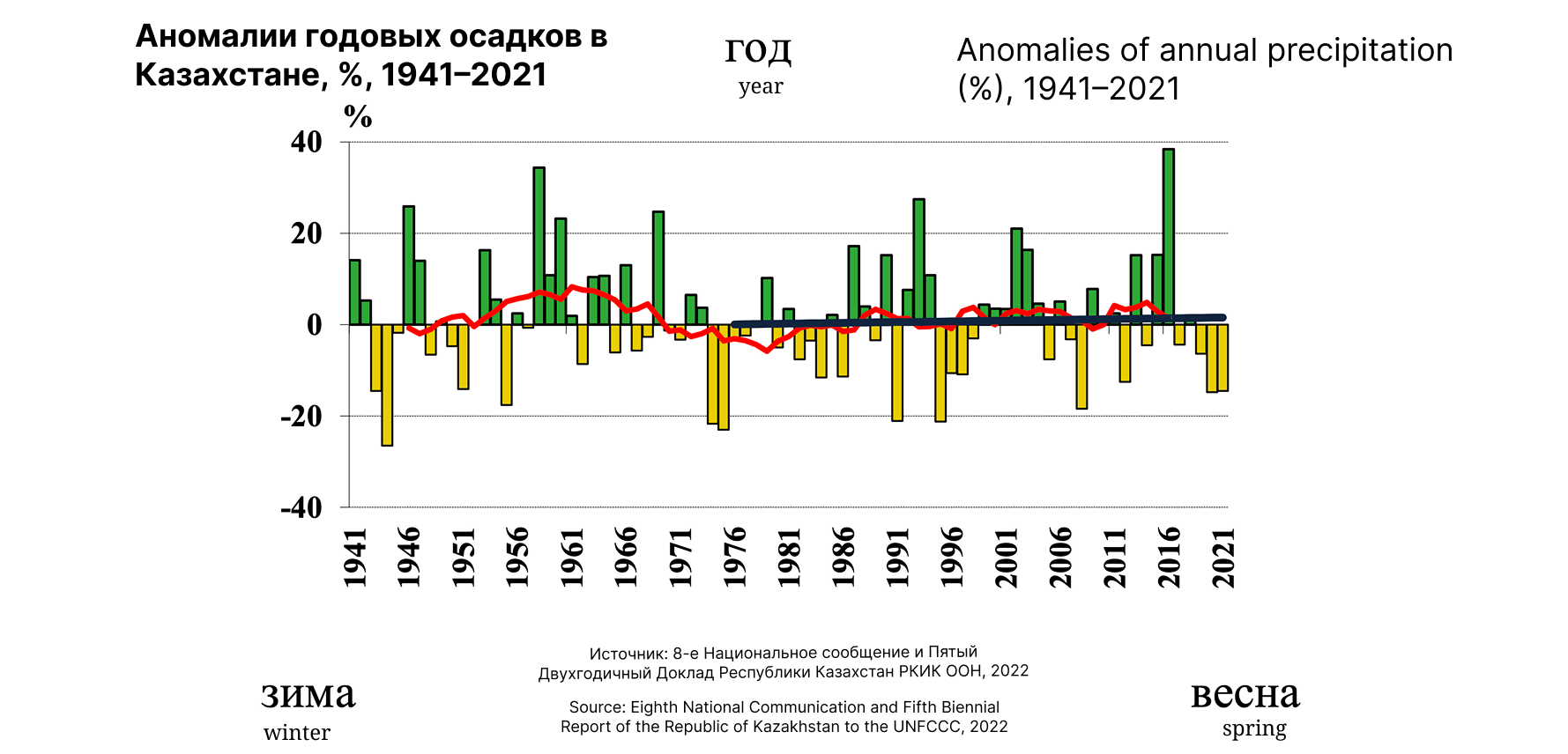

An interesting paradox has emerged: even as glaciers melt, the snow cover in the Altai Mountains has increased by 72% in the last 30 years. But this snow now melts faster and earlier, fueling spring floods instead of the steady summer water supply that once fed the rivers.

In Kazakhstan's arid regions, the situation is dire: 90–95% of the annual river flow comes solely from spring snowmelt. When this snow melts too early, the summer is left dry and waterless.

A Melting Foundation

Beneath the mountains lies another hidden water reservoir: permafrost, covering about 105,000 square kilometers. This underground ice world is now beginning to thaw.

From 1974 to 2018, permafrost temperatures have risen by 0.01°C per year. The thickness of the 'active layer' (the part that thaws each summer) has doubled from 3 to 6 meters - a 23% increase since the 1970s. At the Akshyrak borehole, ground temperatures 20 meters below the surface have risen by 1.9°C in just 36 years.

Degrading permafrost dramatically alters the movement of underground water, leading to serious repercussions for water resources. For example, in the Irtysh River basin - one of Kazakhstan's largest - the summer baseflow has declined by as much as 15%.

The reserves of underground ice in the Inner Tien Shan are estimated at 56 cubic kilometers - 62% of the total glacier volume in the region. When this permafrost melts, it will transform the entire subsurface water system.

A Changing Climate, Plain to See

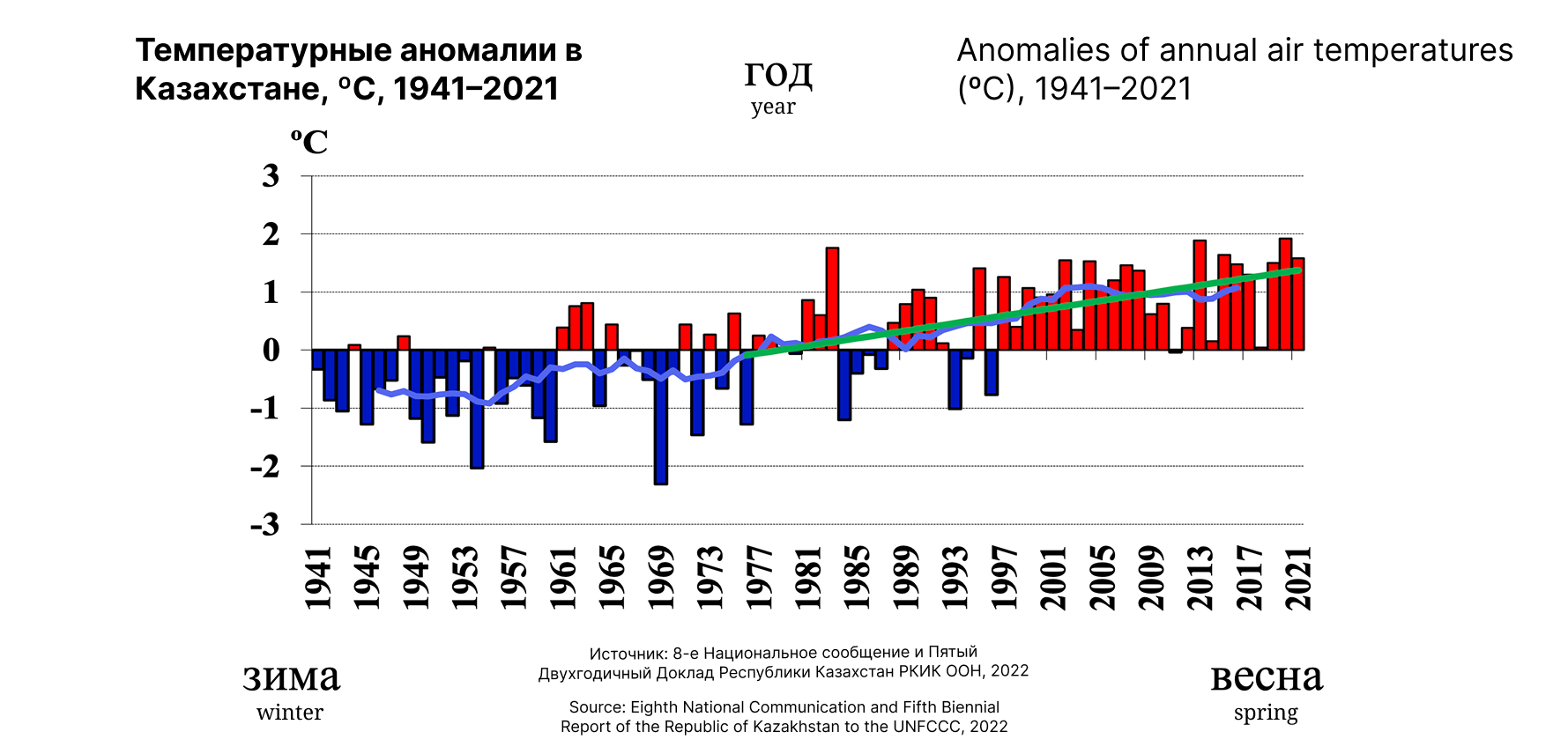

Over the last 30 years, the average annual temperature in Kazakhstan has increased by 0.9°C. Days with extreme heat - above 30–35°C - have become much more common, especially in the south and west.

Winter temperatures are climbing the fastest. This is particularly critical for the survival of the cryosphere. Paradoxically, winter precipitation in the Altai has risen by 15–20%, bringing more snow that then melts away sooner in spring.

Looking to the Future

Scientific projections are sobering. By 2050, Kazakhstan's glaciers may lose up to 50% of their mass; by 2100, they could lose 50% of their volume and 33% of their area - even under moderate warming scenarios.

By 2100, winter precipitation could increase by 20–35%, particularly in the north, leading to stronger spring floods. Even in 2024, flooding submerged 12 towns and 15,000 hectares of farmland in the Kostanay region.

What Does This Mean for People?

In Kazakhstan's mountainous areas - where the cryosphere is formed - 23% of the country's population lives, and almost half of its economy is concentrated. Major cities like Almaty and Shymkent directly depend on mountain water resources.

Shrinking glacier flows mean there will be a critical shortage of water in summer, just when it's most needed for farming and energy. Rivers fed by glaciers supply around 30% of the country's hydropower.

Meanwhile, rapid spring melt brings the risk of floods, and permafrost degradation leads to landslides and changing groundwater levels.

A Call to Action

The story of Kazakhstan's cryosphere is not merely a collection of scientific facts and statistics. It is a story about how our world is changing, about the gradual disappearance of natural systems that have supplied water to people for millennia.

Glaciers, snow, and permafrost are not just part of beautiful mountain scenery. They are vital infrastructure, crafted by nature, sustaining millions. And this infrastructure is collapsing before our eyes.

Understanding these processes is the first step toward adaptation. While there is still time, it is crucial to prepare for new realities, find ways to use water more efficiently, and protect what can still be saved.

Go Back

Go Back